Since when did the standard for protection in combat become a leather bikini?

Or if not that, there’s always a breastplate so sculpted that it would deflect blows into the center of the chest, potentially killing its owner.

Fantasy armor for women can be a little heavy on the fantasy, light on the armor. Image from: Stahlgilde.com.

I like a well done woman warrior character, but I’m not alone in thinking that there have got to be some more realistic costume options out there.

When bringing any fantasy character to life, I try to pass it through a “real-world filter” so that the resulting costume, accessory, etc. will be both functional and attractive. To do this, I usually start each new project by looking for historical precedents for the character.

This can be problematic when creating a woman warrior costume, though, since history hasn’t left us many examples of female armor.

Still, there has to be something out there. This post is dedicated to finding and sharing whatever design principles women warriors of ages past have left behind for us.

A lot of the information I’ll share here is drawn from the book The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World, by Adrienne Mayor. For those of you wanting to fact-check me, I’ll mark with an asterisk (*) when this book was where I got my information.

Did Women Warriors Really Exist?

Before I can go drawing costume tips from factual female fighters, it’s important to decide whether there actually were any or whether such amazon warriors exist only in the realm of fantasy.

Now, throughout world history a number of high profile female military leaders have arisen and done some amazing things—women like Joan of Arc, Nakano Takeko, Grace O’Malley, and Trieu Thri Trinh—but most of these ladies each seemed to be more the exception than the rule in their societies. What’s more, none of them left their armor behind for study.

Vietnamese military leader Trieu Thri Trinh is said to have worn golden armor and carried two swords astride a huge war elephant…but none of these have survived to this day. Image from: listverse.com.

So, are there any examples of cultures where warlike women were more common? This is actually a bit of a controversial topic.

Dem Bones, Dem Bones, Dem Dry Bones

Historically, war has been considered to be strictly the domain of men. Operating under this assumption, years of archaeologists who discovered bodies buried with swords called them “warriors,” and assumed they were male.

I mean, when you discover a grave gated by two giant iron lances with spears and arrows flanking a body bedecked in a massive armored belt, you figure you’ve stumbled on the tomb of Genghis Khan!

More recently, however, researchers have been going back over these finds, and examining the bones more careful for skeletal signs of gender. Some have even done DNA testing.

One way to determine the gender of a skeleton is to look at the pelvis. A male example is on the left; female on the right. Image from: allthingsaafs.com.

In some locations this has led to the surprising finding that many of the bodies buried with weapons were actually women…including the warrior whose tomb I mentioned above (not Genghis Kahn, after all). In Scythia (an important location we’ll get to later), up to a quarter of female burials have been classified as warriors.*

Evidence of Combat

Still, being buried with weapons doesn’t necessarily make you a warrior. Battle wounds on the skeletons make a much more convincing argument. For example, the warrior I’ve been describing had battleaxe wounds in the skull and a bent bronze arrowhead stuck in her knee.*

A single wound might mean the woman was a hapless villager slain in one hit, but multiple wounds paint a picture of intense hand-to-hand combat. For example, forensic analysis of female graves in Tuva (southern Siberia) revealed the following:

“Several women had healed fractures consistent with falls from horses. Battle wounds were mostly to the upper body, indicating combat on equal ground or on horseback. At least 4 females had suffered left forearm fractures, most likely from combat… One of them…also had a fractured rib and ‘boxer’s fractures’ of the right hand, probably from ‘dealing a blow’ during a fight. A broken nose and other facial fractures…were also attributed to ‘interpersonal or intergroup violence.’ About 24% of the head fractures with blunt weapons had been sustained by women. Typically the damage was on the left side of the skull, indicating ‘hand-to-hand combat when facing a right-handed opponent.’

Figure from: The Amazons*

“[Two female skeletons] showed evidence of multiple slashing-sword wounds while in motion and facing an opponent… One warrior woman sustained several nicks and cuts ‘indicative of free-moving combat,’ that is, sword fighting with a foe. The location and direction of the slashes suggest that she ‘was actively engaged in combat…wielding a weapon making it difficult for her opponent to make a clean fatal stroke.’ The other woman had a single sword slash to the thigh, and had been healed… The battle scars and weapon trauma displayed by female skeletons show that ‘warfare was not an exclusive male activity,’ although we cannot know in every case whether the individual was a fighter or a victim.”*

In summary, were there ancient cultures where hunting and fighting women were commonplace? In a word: Yes.

Ancient Greece: The Amazons

Now that we know female warriors existed, lets look at some of the cultures that give clues as to how they might have dressed.

The earliest depictions of women warriors are Greek vase paintings of Amazons—fierce and barbaric female warriors.

This vase from circa 450 BC shows Amazons on horseback spearing Greek warriors. Image from: Tumblr.com.

In these images, Amazons are depicted as wearing long tunics fastened by wide belts. Their heads were either uncovered or clad in soft caps. Their feet were bare or booted and above them they wore trousers or leggings patterned with geometric designs. In fact, the Greeks actually believed that trousers were invented by Eastern warrior queens and the fact that men and women wore the same attire in these cultures was taken as a sign of their barbarism.*

The Greeks may have been accurate about the origin of trousers—the earliest preserved specimens are found in the graves of horse-riding men and women of the Tarim basin, circa 1200-900 BC. For a horse-centered culture, trousers were infinitely more practical than togas.*

In vase paintings, the Amazons do indeed seem inseparable from horses. Their weapon of choice seems to be a spear, giving them adequate range for effective horseback combat.

But does all of this really mean anything? After all, the vase paintings are just illustrations of local myths and legends, just like fantasy paintings today. Surely the Amazon culture didn’t really exist…or did it?

Scythia: Horse-masters of the Steppes

To the East of Greece, there was in fact a culture that matches the Amazonian description: in the steppe lands around the black sea lived a race of horse-riders known as Scythians.

Map of ancient Scythia. Image from: Worldfinancialreview.com.

The territory of the Scythians was broad and they roamed it as nomads. Expert hunters and bowmen,* no desert was so lifeless nor mountain so forbidding that it could contain them.

To the Greeks these wanderers must have seemed uncivilized—even barbaric. Just as the Greek paintings depicted, Scythian men and women alike wore pointed caps, tunics, thick leather belts decorated with iron plaques, and trousers or long skirts hiked up for easy riding.*

Artist’s reconstruction of a Scythian warrior woman.

In addition to their affinity for horses, Scythians also trained golden eagles to hunt for them, and at least one Scythian female has been discovered buried with a thick leather falconry mitt on her left hand.*

This tradition of aerial hunting continues to be practiced in modern Kazakhstan (a place with special significance to me), where well-trained golden eagles are even capable of taking down wolves.

13-year-old Ashol Pan is keeping alive the centuries-old Kazakh tradition of female eagle huntresses. Image from: Dailymail.com.

It is in the Scythian lands that the majority of archaeological evidence for women warriors has been found. This area also offers us our first well-preserved example of female armor.

In 1969 a huge burial mound 60 meters in circumference was discovered in Issyk, Kazakhstan. The mound contained a crushed skeleton buried in a 2-foot-tall golden headdress and a fabulous tunic covered in around 3,000 golden elements arranged in a scale-like pattern. This skeleton also had a dagger and a long sword with scabbards decorated with golden horses and elk.

Because of these weapons the find was quickly popularized as the Golden “Man” of Issyk.

Reconstruction of the ceremonial dress of the Golden “Man” of Issyk. Note the similarity to the geometric tunic patterns seen on Greek paintings of Amazons. Image from: Almatyregion-tour.

The thing is, along with a sword and a dagger, the Golden “Man” also possessed a bronze mirror, a spindlewhorl, and many beads—items almost exclusively found buried with females, and particularly priestesses.

Exact gender evidence from this ancient big-shot’s crushed bones is not available, but these post-mortem accoutrements have led many to believe that the Golden Man of Issyk is in fact a “Golden Princess.”

Not every Scythian woman could be a Golden Princess, but there were still ways for the poorer class to stay in style. In one Scythian mass grave, a pair of trousers were discovered which were covered in beautiful embroidery. These pants appear to have sewn together from pieces of a wall hanging plundered during a Scythian raid on Baktria.*

Europe: One Size Fits All

Scythian women may have been the original Amazons, but if you’re looking to build a lady warrior cosplay, chances are you’re hoping for a more European-inspired look.

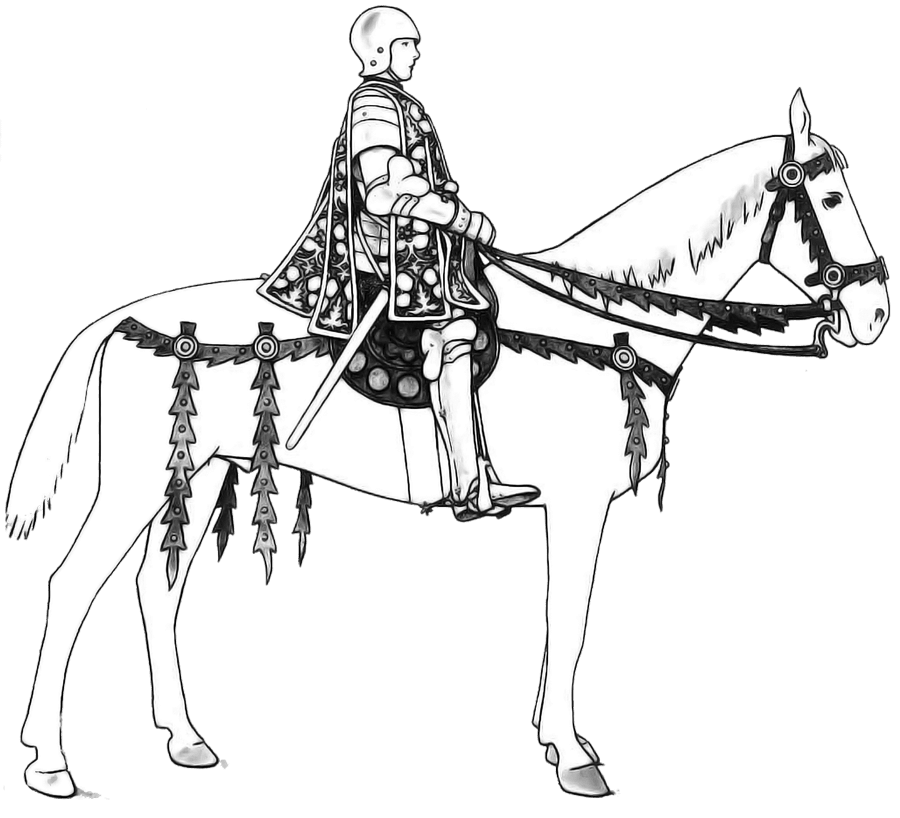

Unlike Scythia, however, in medieval Europe gender roles were more distinct, and for a woman to don armor and join in combat was exceptional. There are literary sources which mention women participating in combat, a few cases of knight-like status given to 10th- to 15th-century women and some imaginative medieval illustrations of warrior women of legend, but to date no image has been discovered of a middle ages woman in armor that was made during her lifetime.

We may not need these images, though. Contemporary writings tend to describe warrior women as wearing exactly the same thing as men, and we have plenty of examples of male armor from the period.

So, if a woman fought in the days before plate armor, then she probably wore a chainmaille hauberk…just like the men.

Famously, King Charles VII of France commissioned a suit of plate armor to be made specifically for Joan of Arc.

Based on contemporary armor trends and the few descriptions we have, Joan of Arc’s armor may have looked something like this. Image from: jeanne-darc.info.

The armor cost 100 écus (not especially extravagant) and was described as a “white harness.” “White” means that there were no decorations on the armor and “harness” means that it was an all-in-one suit, rather than a set of removeable pieces.

A modern woman in unembellished “white” plate armor.

Joane’s custom armor was given to the town of Saint Dennis in ex voto and disappeared from history after that.

Tradition holds that this bascinett was worn in battle by Joan of Arc. Image from: Metmuseum.org.

Over the years, several people have claimed to have discovered the suit—usually based on battle damage corresponding to Joanne’s wounds—but so far none of these claims have withstood serious scrutiny.

Scandinavian “Shieldmaidens”

Farther north, Norse mythology is replete with references to Valkyries and “Shieldmaidens,” such as Alfhild, who was both a princess and a pirate.

In this area of the world, numerous skeletons have been found of women buried with weapons (and men with jewelry for that matter), and there are some historical references to warrior women. One ancient Icelandic law code, for example, makes provisions for professional female warriors called Skjoldmø (Shieldmaidens).

None of this evidence is very concrete, but on the whole it suggests that in archaic Norse culture gender roles may have been more fluid than in neighboring countries.

So, if women warriors did exist in Scandinavia, what did they wear?

Unfortunately very little clothing has survived from Scandinavian burials, but the information we have indicates that like the rest of Europe, northern Shieldmaidens likely donned the same armor as their male counterparts.

In Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings,” Eowyn follows the shield maiden tradition of dressing in man’s armor to join in the fight for Minas Tirith.

Around the 12th century, Danish historian and author Saxo Grammaticus described Shieldmaidens thus:

There were once women among the Danes who dressed themselves to look like men, and devoted almost every instant of their lives to the pursuit of war, that they might not suffer their valour to be unstrung or dulled by the infection of luxury. For they abhorred all dainty living, and used to harden their minds and bodies with toil and endurance. They put away all the softness and lightmindedness of women, and inured their womanish spirit to masculine ruthlessness. They sought, moreover, so zealously to be skilled in warfare, that they might have been thought to have unsexed themselves.

This description paints a picture of women who abhorred traditional feminine roles and values and aligned themselves with a more masculine identity. If this truly was the case, then it seems most likely that among Norse cultures all warriors—male and female alike—would have looked pretty similar going into battle.

Japan: Onna Bugeisha

No review of female warriors would be complete without mentioning the contributions of the Japanese Onna Bugeisha (“female martial artist”).

There are many Japanese legends about early warrior women such as Tomoe Gozen. It is unclear how much of these stories is fact and how much is fiction, but it is certain that they played a big part in creating a national image of brave women wielding naginata to defend their homes when the men had gone to war.

The naginata was a long, spear-like weapon with a curved blade on the end. This was a sensible weapon for a female warrior. A male opponent might have superior size and strength, but this could be circumvented by keeping him at arm’s length.

Image from: Wikimedia commons.

Tomoe Gozen may or may not have been a real person, but in later Feudal Japan there are plenty of more factual accounts of women (such as Nakano Takeko) fighting both at home and on the battlefield. DNA studies on multiple mass graves have found about one third of the bodies to be female. Since these graves were from open warfare and not siege situations, it is reasonable to assume that significant numbers of women were present on the battlefield, and may even have been combatants.

The feudal period was long (1185-1868 AD), and gradually the female martial tradition grew into formal schools which instructed women in naginata use.

Another delightful side-effect of the lengthy feudal period is that it stretched all the way into the age of the camera, offering us a photographic record of Japan’s warrior women.

A colorized photo of a late feudal Onna Bugeisha. Image from: historydaily.org.

One recently discovered suit of armor has several fascinating modifications to make it more suitable for use by a woman.

Image from: Bonhams.com.

The armor pictured above features enlarged space in the helmet (for extra hair), a unique design which opens in the front allowing the armor to be donned independently (to avoid embarrassment) and deerskin lining under all the armor elements so as not to damage a silk kimono worn underneath.

Africa: Amazon Army of Dahomey

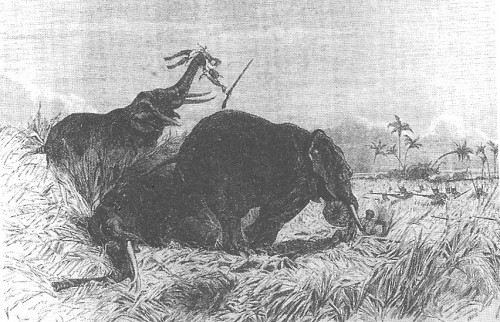

An equally recent and well-documented group of women warriors existed in Africa between the 17th and 19th centuries AD. These were the legions of the kingdom of Dahomey—perhaps the largest organized group of exclusively female warriors in history.

The origins of this women’s army are somewhat unclear. Some believe they began as Gbeto elephant hunters. Others feel they were first stationed as a palace guard made up of their king’s third-tier wives.

Female Gbeto elephant hunters. Image from: Smithsonianmag.com.

Regardless of the origin story, the Dahomey women came to be a vast and powerful military organization, fighting for king and country with legendary ferocity.

These warriors underwent brutal training, including harsh physical hardening and emotional “insensitivity training” involving the slaughter of prisoners to prepare girls to kill without mercy on the battlefield. This savage lifestyle was appealing to many women because it elevated them from a life of forced drudgery to being elites with free access to alcohol, tobacco, and slaves.

There are a number of pictures of the Dahomey warriors. These show them wielding muskets and wearing long skirts made of multiple pieces of fabric, with an “armored” top covered in white sea shells (click the picture for the full-size image).

The trouble with these images is that they were all taken in the late 19th or early 20th century. After 200 years of military expansion, Dahomey was defeated, and their lands taken, by the French in 1890. The Dahomey warriors (men and women alike) were almost immediately taken to various countries as objects of curiosity. They appeared at London’s crystal palace in 1893, where they performed imitation combat and where many of the existing pictures were taken.

During this London period, the Dahomey warriors drew tremendous crowds, partly to see their curious costumes. Accordingly, the police ensured that they were “well wrapped up.”

July 1893 railway timetable advertising the Dahomey spectacle. Image from: Africanamerica.org.

Because these pictures were taken when the warriors were dressed to suit the tastes of a European audience, it is hard to say how much of their get-up is authentic and how much is just costuming.

More reliable are accounts and illustrations of these “Amazons” prior to their defeat. In 1861, an Italian priest named Father Francesco Borghero visited Dahomey, where the king showed off his prized women warriors by having them stage a mock battle. Author Stanley Alpern summarized Borghero’s description of the spectacle thus:

“At some distance from the barricade were about 3,000 armed and uniformed women. Two or three hundred of them carried giant straightedge razors folded into wooden handles. It was said that these weapons, wielded with both hands, could cut a man in two at the middle with one swipe. All the other warrioresses were equipped with flintlock muskets and swords.

“The women wore battledress: a half-sleeved rust-colored tunic cinched at the waist by a cartridge belt, and shorts of almost knee length. Narrow white headbands were tied at the back. Some amazons wore copper or gemstone bracelets and anklets. All were barefoot.”

The priest went on to describe a young female general who later visited with him:

“She was aged about thirty, slender but shapely, proud of bearing but without affectation.”

Borghero’s report is pretty consistent with these 1851 plates depicting Dahomey female officers:

1851 illustrations of Dahomey officers. The women on the right are sporting “horns of office.” Images from: Smithsonianmag.com.

The clothing seen here—tunics, trousers, belts and bare feet—is interesting in its similarity to the Amazons seen in Greece and Scythia, even though the cultures are separated by thousands of miles and just as many years.

Together, the 1893 photos and the 1851 illustrations provide two different takes on the dress of one incredible case of female military might.

Summary

Women warriors may not be frequently mentioned throughout history, but they did exist, and we do have some idea what they wore.

So, whether it’s an elvish princess or a viking shieldmaiden, the next time you’re building a female warrior costume, consider the following historically-inspired suggestions:

- Outfit your character with long- and medium-range weapons such as spears, naginata, or bows and arrows.

- Ally yourself with an animal friend like a horse or eagle.

- Consider a scythian look with tunic, trousers, a large armored belt, and geometric patterns.

- Build your clothing out of embroidered cloth plundered from the last village you sacked.

- Follow the African tradition of fighting with bare feet (plus maybe a gemstone anklet).

- Line your armor with fur to protect more feminine clothing underneath.

- Wear a pointed cap or a helmet with plenty of room for your hair, or simply pull it back with a headband.

- Look at what men were wearing in the period you’re interested in, and imitate that.

- Design armor that can be put on independently to avoid embarrassment on the battlefield.

- Avoid skimpy or overly-sculpted chest pieces that are just downright dangerous!

Put it all together and you just might end up with something that looks like this:

An excellent Scythian costume—feminine, fierce, and historically grounded. Image from: Facebook.

Getting some inspiration? I’d love to see what you create!