Chainmaille armor ought to be the cosplayer’s best friend. It’s time consuming, sure, but you get a huge realism payoff and—compared to a lot of other types of armor smithing—chainmaille is relatively cheap and simple to make.

Most of the armor I make today is crafted with the same simple tools I used when I was 13 years old: a dowel, a hand drill, inexpensive wire, some shears, and two pairs of pliers.

There are plenty of instructional videos and pdf’s out there that can teach you the basics of using these tools to start making maille. Here’s one example (my own approach is actually even simpler than this, so maybe I’ll put my own video out there some day):

Now, the question is, if I’m using the same basic tools and techniques now that I did over a decade ago, why does my maille look so much fancier than what you see in the video above?

One word: weaves.

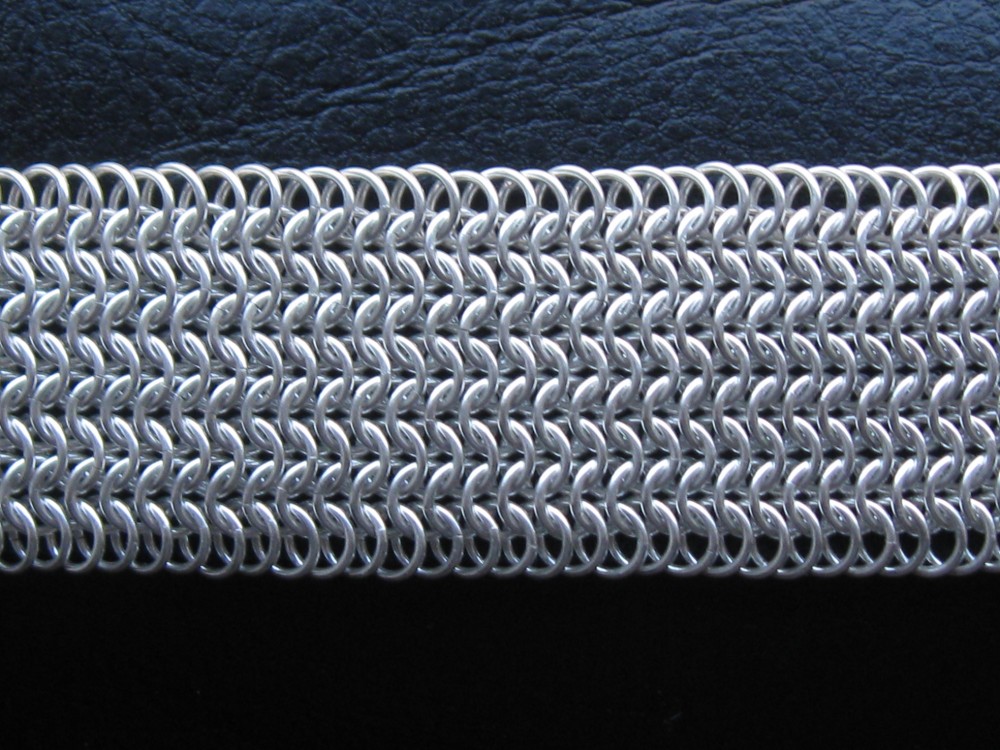

Weaves are the patterns an armorsmith uses to connect the tens of thousands of rings in a chainmaille suit. The most common weave is called “European 4-in-1.” It’s the pattern seen in the video above and you see it in 90% of the armor out there.

On the rare occasions when you see somebody wearing a different weave, chances are it’s just European 6-in-1, which is practically identical—just a slightly denser variant.

A European 6-in-1 sample. Image from: Craftychristian.com.

These traditional weaves aren’t bad to start with and learn the basics, but if you want your armor to stand out, you’ll need to be a little more creative.

Take my recent Faramir costume, for example.

This hauberk features 5 different weaves, each selected for their weight, density, flexibility and appearance to create the most practical and attractive overall presentation.

The good news is, there are thousands of fun and exciting weave patterns available out there. When starting a new project, my favorite database to search is the Maille Artisans International League (M.A.I.L.) where you can find numerous weave designs often with example pictures and high quality instructional articles.

Searching through a site like this can be a little intimidating though, I admit. The purpose of this article is to teach you the lingo you’ll need to understand the types of weaves out there and to choose the perfect one(s) for your next project.

Ready for your crash course? Then let’s get crashing!

Weave Forms

Chainmaille is a very versatile art form, and there are specialized weaves for everything from jewelry to sculpture. Most of the weaves you’d consider using for cosplay, however, will fall under three different categories of form or appearance: Chain, band, or sheet.

Chain

Chain weaves are just what their name implies: repeating ring patterns that grow into a long thin chain.

A few example chain weaves. Click the links to see descriptions and tutorials of each. 1. Ash’s Bizantine, 2. Box Chain, 3. Celtic Spiral Knot, 4. Spiral 6 in 1, 5. Half Persian 8 in 1.

Weaves like this are great for jewelry and other accessories. They are especially useful in necklaces but can also be used on bags, small bracelets, and even sometimes the borders of an armor project.

For example, in the picture above, a simple brass box chain weave is used as an effective sleeve border.

Band

Band weaves are just as self-explanatory. Their patterns form a long band, with additional rings being added lengthwise, but not expanding on the sides.

I’m fond of using band weaves as borders in armor, but they are also very useful for bracelets, belts, and other fancy straps. My Faramir costume even featured a band weave on the back in an advanced form of inlay to create the image of the white tree of Gondor.

A complicated inlay pattern with a band weave set in a sheet weave. Click here to learn more about the weaves I used in this costume.

Overall, band weaves are like chain weaves on steroids. They’re bigger and buffer, but they’re still not armor.

Sheet

Sheet weaves will make up the bulk of an armor project. They can expand in four directions endlessly to make clothing of any size you need.

1. Trinitymaille, 2. Aura Sheet, 3. Elfsheet, 4. Dragonscale, 5. Moorish Rose, 6. Half Persian 4 Sheet 6.

The classic European 4-in-1 and 6-in-1 weaves I’ve already mentioned are both sheet weaves, but there are lots of other options out there.

You can do a lot of cool things with sheet weaves, including changing the colors of the rings you use to create images on your costume.

In this shirt, aluminum and brass rings alternate to create the image of a Celtic trinity knot.

Although sheet weaves lend themselves to armor very well, they can also be used for many other things. I’ve seen them in jewelry, as decorations on furniture, and even in sculptures.

Weave Families

In addition to the general shape of a weave, there are also several weave “families” out there, grouped together by the type of pattern used to connect the rings.

European

European weaves are what most people think of when they picture chainmaille armor. Rings connect to each other in a square pattern with rows of rings at alternating angles, vaguely resembling the pattern of threads in a knitted sweater.

When viewed from the side, these rows of rings are oriented such that they lie almost flat against the wearer, like so:

There are many variations on European weaves, but they all look fairly similar to each other.

You may notice that the “Dragonscale” weave above (#3) appears to break the rules of European weaves since all the rings seem to slant in the same direction (like reptile scales…thus the name). There are several Dragonscale variants out there which all achieve this same visual effect, but at their heart they are really just a European 4-in-1 weave. Extra links are merely added to this base to disguise the rows which aren’t going in the “right” direction.

Japanese

European weaves originated in Europe (big shocker, I’m sure). Ancient Asians also developed a form of armor made from interconnected rings, but it took a very different form.

Unlike the flat European weaves, in Japanese weaves the rings are usually offset from each other by 90 degrees, just like a normal chain (like what you’d see on a ship’s anchor). Because of this orientation, Japanese weaves do not form rows like their Caucasian counterparts. Rather, they grow in geometric units like hexagons, pentagons or octagons.

This can create a very beautiful latticework to look at, although it has the disadvantage of having many rings face directly outward, with open circles providing less protection against arrows.

Persian

Although the oldest known chainmaille suit was in fact found on a soldier from Persia, as far as I know he was wearing a European weave. Persian weaves are among the most beautiful out there, but despite their name, they are a modern invention and are not actually from Persia.

1. Half Persian 3 Sheet 5 Crossover, 2. Half Persian 4 Sheet 6 Crossover, 3. Half Persian 4 Unbalanced Sheet 8 in 1, 4. Paddy’s Sheet, 5. Persian Ridgeback.

These lovely patterns are quite complex and can be difficult to get the hang of, but they are extremely rewarding once mastered. Most Persian patterns form bands or chains, but a few clever souls have managed to turn them into sheet weaves.

Although Persian sheet weaves do have rows and rings at obtuse angles like your standard European weaves, they are different from European weaves in that they are biased. Unlike the box-shaped European weaves, biased weaves are slanted, so the weaves grow in tilted parallelograms instead of in a straight line.

This can make combining Persian and European weaves tricky, but it can also have some distinct advantages. For example, this chainmaille shirt was made from the biased weave, “trinitymaille.” The cosplayer has taken advantage of the weave’s natural angles to create a feminine V-neck and peaked ends at the bottom of the shirt.

There are a lot more weave families out there invented by clever artisans, such as Voodoo weaves and Mage weaves.

By the Numbers

Once you know the basic form and family of a weave, you can search a database with terms like “Persian sheet weave” and have a pretty good idea what your results are going to look like. Even so, there will still be a lot of variety out there. One of the main things that differentiates one weave from another inside the same family is the number of rings in each repeating unit.

Weaves are often named with numbers which describe the smallest repeating unit of connected rings used in the pattern. For example, in European 4-in-1, four rings pass through each ring. Even if all you had was a tiny sample like this…

…it would still be European 4-in-1. Add or subtract a ring, however, and you wouldn’t be able to make the same weave.

As you might imagine, European 6-in-1 follows the same rule, but with each ring attached to six others, instead.

As you can imagine, this increases the density and weight of the weave quite a bit.

For this reason, it can be very useful to look at the numbers which may be attached to a weave’s name. This will give you a basic idea of how thick the weave will be. The more rings passing through each other, the greater the protection will be, but the weave is also likely to become more heavy and less flexible.

This European 10-in-1 weave has the same basic structure as the 4 in 1 above, but there is little space between the rings, resulting in maximum protection, but minimum flexibility.

Most weave numbers tell you how many rings go through each other ring, so the second number is usually 1. In some cases, however, the smallest repeating unit of the weave is more complex than this, so you might see numbers like “6-in-2.”

Special Terms

The information I’ve already presented is enough to help anybody find their way through the majority of basic chainmaille weaves, especially those which are useful for armor. This section will cover certain terms you might also run in a weave’s name. These terms describe special techniques that go beyond just passing one link through another.

These techniques are most often used with advanced jewelry weaves, but just because they’re uncommon that doesn’t mean they’re necessarily hard to learn. If you’re interested, I encourage you to read on and become a true maille master!

Orbital Rings

Most weaves are made up of rings that pass through each other. But in some cases, rings go around each other instead. When two or more rings link through each other and another ring surrounds that juncture, it is called an “orbital ring” because it almost looks like the rings around a gas giant planet.

This chain weave is an excellent example of “orbital” rings.

Captive Rings

Like an orbital, a captive ring doesn’t pass through any other links.

Each unit of this chain weave is designed to hold two rings “captive.”

Rather than floating outside connected rings, however, these rings are trapped within a latticework created by the rest of the weave.

Kinged Rings

Perhaps the easiest way to make a weave denser is to “king” it. This doesn’t require learning a new weave, you just take a weave you already know, and every place you would have put one ring, just put two instead.

This technique might get its name from the game of checkers, where you “king” a piece simply by stacking another on top of it.

This is the same unit of European 4-in-1 I showed before, but this time I’ve “kinged” each golden ring with a copper one.

So, if the only weave you know is European 4-in-1, simply double it up and you’ll have yourself some fancy King’s Maille!

Image from: Mailleartisans.org.

Previously, I mentioned that some weaves are named things like “8-in-2.” When a weave’s second number is 2, there’s a pretty good chance that kinging is involved.

Scaled Rings

Kinged rings do a good job at increasing the density of a weave, but not all weaves take to kinging well and sometimes they can end up looking thick, shaggy and disorganized.

“Scaling” is a more aesthetic approach which still doubles up rings, but instead of using links all of the same same size, scaled patterns fit small rings perfectly inside larger ones, allowing the weave to maintain a nice flat profile.

This weave is essentially just the King’s Maille seen above, but the inset scaled rings give an attractive, smooth appearance.

Aspect Ratio

Choosing the perfect ring sizes for concentric scaled weaves can be tricky. In fact, it can be a struggle to choose the right ring dimensions when working with many weaves.

If your wire is too thick or your ring is too small, you may not have enough room to fit all of a weave’s required links through each other, or your weave may end up too stiff and rigid to wear. On the other hand, if your wire is too thin or your rings too large, then the weave will look thin and filmy and the visual pattern won’t register well.

You can figure out the perfect ring dimensions for each weave on your own through trial and error…or you can learn from others who have done so before and use the aspect ratio they recommend.

An “aspect ratio” (AR) is a way of combining the two critical dimensions of a chainmaille link: interior diameter (the width of the inside of the ring) and wire diameter (also known as its gauge). The formula for this magic ratio is:

AR = ring interior diameter / wire diameter

Because this number is a ratio, a big ring with big wire and a little ring with little wire can have the same AR, as explained in this diagram from The Ring Lord:

When searching through weaves on M.A.I.L., the ideal aspect ratios for each weave are listed right next to their names, as I’ve marked in yellow on this screenshot:

Even knowing this number would still be a huge pain if you then had to go pull out a pair of calipers, measure the thickness of your chosen wire in millimeters and derive the correct interior diameter of your wire by reverse-engineering the AR equation. Thankfully, all this work has already been done for you too!

So, if I wanted to make the above Byzantine chain and had 16 gauge wire on hand, to figure out the best accompanying ring diameter all I would have to do is:

- Open the link to the weave summary (click on the blue words “Byzantine”)

- Find the aspect ratios on the left hand side of the page, and

- Hover over them in order to see a chart of wire gauges and ring sizes that can make each AR.

This list says that 11/64ths of an inch is the ideal interior diameter to match my 16 gauge wire. Obviously, I’m not going to find a lot of dowels this size to make links, but it’s okay to fudge a little. In a situation like this I would just bump up the diameter to the closest dowel size I have—3/16″—and the weave should still work just fine.

Sometimes, you may run into weaves with a bunch of different aspect ratios listed, like this one:

This means that there are multiple ring sizes (and possibly wire sizes) required to make the weave. If you’re a beginner, this could be pretty challenging to take on, so you might want to stick to weaves with only one AR at first.

Summary

Are you overwhelmed yet? Don’t worry, you’ve probably learned more than you think.

For example, if I give you a random weave name, like 8-in-1 Orbital Sheet, you can now tell me all about it without ever even seeing an example:

- 8-in-1: The basic unit of the weave will have 8 rings going through 1 ring.

- Orbital: The weave will include “orbital” rings that don’t pass through other rings, but are trapped outside of them.

- Sheet: The weave can grow indefinitely both length-wise and in width.

Lo and behold, you got it right! Here’s what that weave (one of the more complicated weaves out there) looks like:

You’re getting to be an expert maillesmith already!

However, if your memory’s a little foggy don’t worry about it. I created this article as a reference for you so you can always check back with terms you don’t understand.

Of course, I haven’t covered everything there is to know about chainmaille. I could go on for days about hoodoo weaves, voodoo weaves and mobius balls, but what I’ve chosen to write contains the basic lingo you’ll need to find fantastic weaves for your next fantasy creation.

Feeling inspired? Start searching for new and exciting weaves to make your projects totally unique, or if you want more of a guided tour then try checking out a few of the dozens of weaves I’ve linked to in this article. Have a great time learning this fantastic hobby and if you have more questions comment below! Maybe I’ll write another post to address your query!